For the last couple of weeks, while Joshua has been preparing for his bar exams, I have been busy doing things around the house and yard for my mother and father.

Among other projects, I conducted a deconstruction of my mother’s kitchen, taking apart every item that might be disassembled and subjecting it to a thorough and detailed cleaning. Somehow I managed to reassemble everything without, as far as I know, breaking or damaging anything.

Every floor in the house has been waxed and polished to a standard that would satisfy Admiral Halsey. Every light fixture has been cleaned and polished to a high gleam—even the outdoor light fixtures have been cleaned and polished—and every window in the house washed inside and out.

I performed spot reseeding of the lawn, and I trimmed trees and bushes.

I painted exterior windows and shutters and doors, including the garage doors.

I washed and cleaned the cars.

In fact, I did everything but sweep the chimneys.

I announced that I intended to power-wash the back deck and the back fence, but my mother told me that she would not hear of it.

________________________________________________

On Saturday, everyone in my family will head North for our annual July 4 week at the lake. We shall devote Thursday and Friday to getting our things ready.

Everyone except Josh and me spent Memorial Day Weekend at the lake—Josh and I were still in Boston—but no one has traveled up to the lake since. Josh and I have not been to the lake since July 2009, so we very much look forward to it.

________________________________________________

The dog has been getting lots of trips to the park. In addition to his early-morning romp, Josh and I have been taking him to the park most afternoons. As soon as we return from our afternoon trip to the park, the dog likes to nap.

At home, the dog has a new favorite rest spot in the kitchen, a spot on which he can keep an eye on Josh in the dining room (Josh’s study center) and an eye on my mother in the kitchen. The dog always likes to observe as many persons as possible without moving.

Whenever I have been at work in the house and yard, the dog has joined me, fearful that he might miss something interesting or fun.

He will have a good time at the lake next week. He will sit in the shade and watch what everyone is doing, and join us in our activity whenever something attracts his interest, and bark at passing kayaks on the lake.

Next month will mark ten years since we brought the dog home from the pound. It seems as if it were yesterday that we first brought him home.

He is aging. He can still be very energetic, but for shorter periods than in years past. Rest is important to him now. If we take him out, when we return home he immediately goes to his rug on the kitchen floor and lies down.

He has aged noticeably since Christmas. He is slower to get up after resting on his rug. It appears that he now finds stairs somewhat of a trial. I generally carry him upstairs now, and he does not mind at all—indeed, I think he welcomes it.

He takes two vitamin supplements and two medications, all designed to ease discomfort in his hind legs—he is developing hip problems common in German shepherds bred in America—and his dosages have been increased twice in the last year. We notice his stiffness when he climbs stairs, or when he attempts to jump up on the daybed in the kitchen, the only piece of furniture in my mother’s house on which he is permitted to sit. I generally lift him now when he wants to sit on the daybed—and he is generally content to rest there for an hour at a time, unthinkable three years ago.

His appetite is still good. He never misses meals.

And he remains very, very good-natured, especially with my nephew and niece.

His hearing is deteriorating. He knows the sound of the vehicles of everyone in the family, but he no longer hears the vehicles until they have reached the garage at the back of the house. In the past, he would announce arrivals when vehicles were within half a block of the front of the house.

His eyesight, too, is deteriorating. En route to the park, he is trained to stop at the end of each block and wait for whomever is accompanying him before crossing the street. He now has trouble distinguishing where the sidewalk ends and where the street begins, and this visibly disorients if not upsets him. As a result, he has stopped running ahead on his own to the end of each block; he now prefers to walk alongside his companion or companions the entire way to the park.

We hope to be able to care for him for another one to two years—and longer if his health holds up. Nonetheless, we can see that he is beginning to fail. We know that our remaining time with him will be measured in months, not years.

________________________________________________

Tomorrow we plan to do something unusual for a weekday: we plan to go downtown to see a film and a play.

The genesis of our plan: the fact that Yasmina Reza’s play, “God Of Carnage”, only lasts one hour and fifteen minutes.

“God Of Carnage” is in the current Guthrie repertory, and Josh and I are curious to see the play, and my parents are curious to see the play.

However, because the play is so short, we all decided that we would not make a trip downtown to see the play unless we could pair a performance of “God Of Carnage” with some other worthwhile activity downtown—and, until Sunday, we were unable to identify any other worthwhile activity downtown.

We had been prepared to forego “God Of Carnage” until, on Sunday night, we examined Twin Cities movie listings. We noticed that “City Of Life And Death”, a Chinese film about The Rape Of Nanking, was enjoying a one-week run at an art house cinema in downtown Minneapolis. (The Twin Cities have three art house cinemas: two in downtown Minneapolis; and one in Edina not far from my parents’ house.)

We decided that we would not mind seeing “City Of Life And Death”—and, further, we decided that “City Of Life And Death” together with “God Of Carnage” might make a trip downtown worthwhile.

Consequently, in the middle of tomorrow afternoon, my mother and Josh and I will drive downtown, pick up my father at his office, and catch the 4:10 p.m. screening of “City Of Life And Death” followed by the 7:30 p.m. Guthrie performance of “God Of Carnage”.

It should make for an interesting late afternoon/early evening.

We shall eat out on the way home.

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Saturday, June 25, 2011

Orchestra Conductors At Leisure

Eugene Ormandy, conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony from 1931 until 1936, with his bicycle.

This photograph was taken in the Twin Cities during Ormandy’s Minneapolis tenure.

Mr. and Mrs. Ormandy were known to bicycle together around Minneapolis.

Dimitri Mitropoulos, conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony from 1937 until 1949, with his backpack.

This photograph was taken in the Twin Cities during Mitropoulos’s Minneapolis tenure.

Mitropoulos was surely the lone backpacker in the Twin Cities in the 1940s. Many persons in the Twin Cities viewed Mitropoulos as somewhat of an oddball, although he was the most beloved conductor in Minnesota Orchestra history.

Antal Dorati, conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony from 1949 until 1960, at a University Of Minnesota football game.

This photograph was taken in the Twin Cities during Dorati’s Minneapolis tenure.

Well into the 1970s, persons dressed for University Of Minnesota football games.

________________________________________________

Osmo Vanska motorcycles.

Our Summer Of Musicals Continues

Last night, Joshua and I and my middle brother went to Saint Paul to attend a performance of the Frank Loesser musical, “Guys And Dolls”.

The production was by The 5th Avenue Theater, a theater company in Seattle that specializes in musicals. “Guys And Dolls” was a presentation of The Ordway Center For The Performing Arts, which has sponsored Saint Paul appearances by The 5th Avenue Theater in the past. I believe there is some sort of production arrangement between The 5th Avenue Theater and The Ordway—the director of this particular staging of “Guys And Dolls” hails from the Twin Cities, and The Ordway put up a good portion of the Seattle production costs—and it appears that The Ordway likes importing one of the Seattle productions from time to time (especially in the summer months, when The Ordway’s primary residents are in the off-season).

The Ordway is a busy venue. In addition to serving as home of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Minnesota Opera and The Schubert Club, the Ordway hosts several theatrical presentations each year, most of which are musicals. Some of the theatrical presentations are touring Broadway productions, some are staged by repertory companies (Minnesota repertory companies and out-of-state repertory companies), and some are productions in which the Ordway is producer, creator and originator.

The Seattle “Guys And Dolls” has a two-week stint in Saint Paul, and Josh and I and my brother caught a performance during the final weekend of the run.

We loved the show. “Guys And Dolls” is a very enduring vehicle, primarily because the songs are so good. One hit song follows another in quick succession. The quality of the songs overcomes the old-fashioned nature of the story and the book.

The Seattle production was a good one. The stage design was handsome, the choreography was excellent, the cast was fine, and the orchestral support was vigorous. It would be hard to contemplate a better contemporary mounting of this 1950 gem of the American musical theater than the production we encountered last night.

And yet the local reviews were mostly dismissive (the Pioneer Press being the exception).

The same reviewers that, unaccountably, had lavished praise upon Jungle Theater’s entirely lame production of “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To Forum” (which Josh and I and my brother had suffered through the previous Friday night) carped about the Seattle production of “Guys And Dolls” no end, finding it unimaginative and old-fashioned.

My guess is that local critics were applying one set of standards to Jungle Theater, a local company, and another set of standards to The 5th Avenue Theater, a company from out-of-town. There is nothing else that can account for such vast misjudgments about both shows.

I suspect that, in 2011, it is very hard to get the tone of “Guys And Dolls” right. The character “types” portrayed in the show no longer exist; it must be difficult for contemporary singing actors to recreate arch-types no longer visible (and no longer recognizable). The cast members in the Seattle production came about as close as one has a right to expect today.

Before the “Guys And Dolls” performance, we ate dinner at a French brasserie in downtown Saint Paul.

The restaurant was very fine—some persons insist it serves the finest French fare in the Twin Cities—and we were very pleased with our food.

We ordered broiled oysters; white asparagus soup with pancetta and almonds; and Alaska halibut. We were pressed for time, and had to skip dessert.

Asparagus soup must be in vogue. The previous Friday night, we had had asparagus soup with king crab and lime at an American restaurant in downtown Minneapolis.

We shall have to return to the Saint Paul restaurant—we liked the chef’s attitude expressed in the menu:

We are unable always to accommodate vegetarians, as most French cooking involves eggs, creams and proteins.

The production was by The 5th Avenue Theater, a theater company in Seattle that specializes in musicals. “Guys And Dolls” was a presentation of The Ordway Center For The Performing Arts, which has sponsored Saint Paul appearances by The 5th Avenue Theater in the past. I believe there is some sort of production arrangement between The 5th Avenue Theater and The Ordway—the director of this particular staging of “Guys And Dolls” hails from the Twin Cities, and The Ordway put up a good portion of the Seattle production costs—and it appears that The Ordway likes importing one of the Seattle productions from time to time (especially in the summer months, when The Ordway’s primary residents are in the off-season).

The Ordway is a busy venue. In addition to serving as home of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Minnesota Opera and The Schubert Club, the Ordway hosts several theatrical presentations each year, most of which are musicals. Some of the theatrical presentations are touring Broadway productions, some are staged by repertory companies (Minnesota repertory companies and out-of-state repertory companies), and some are productions in which the Ordway is producer, creator and originator.

The Seattle “Guys And Dolls” has a two-week stint in Saint Paul, and Josh and I and my brother caught a performance during the final weekend of the run.

We loved the show. “Guys And Dolls” is a very enduring vehicle, primarily because the songs are so good. One hit song follows another in quick succession. The quality of the songs overcomes the old-fashioned nature of the story and the book.

The Seattle production was a good one. The stage design was handsome, the choreography was excellent, the cast was fine, and the orchestral support was vigorous. It would be hard to contemplate a better contemporary mounting of this 1950 gem of the American musical theater than the production we encountered last night.

And yet the local reviews were mostly dismissive (the Pioneer Press being the exception).

The same reviewers that, unaccountably, had lavished praise upon Jungle Theater’s entirely lame production of “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To Forum” (which Josh and I and my brother had suffered through the previous Friday night) carped about the Seattle production of “Guys And Dolls” no end, finding it unimaginative and old-fashioned.

My guess is that local critics were applying one set of standards to Jungle Theater, a local company, and another set of standards to The 5th Avenue Theater, a company from out-of-town. There is nothing else that can account for such vast misjudgments about both shows.

I suspect that, in 2011, it is very hard to get the tone of “Guys And Dolls” right. The character “types” portrayed in the show no longer exist; it must be difficult for contemporary singing actors to recreate arch-types no longer visible (and no longer recognizable). The cast members in the Seattle production came about as close as one has a right to expect today.

Before the “Guys And Dolls” performance, we ate dinner at a French brasserie in downtown Saint Paul.

The restaurant was very fine—some persons insist it serves the finest French fare in the Twin Cities—and we were very pleased with our food.

We ordered broiled oysters; white asparagus soup with pancetta and almonds; and Alaska halibut. We were pressed for time, and had to skip dessert.

Asparagus soup must be in vogue. The previous Friday night, we had had asparagus soup with king crab and lime at an American restaurant in downtown Minneapolis.

We shall have to return to the Saint Paul restaurant—we liked the chef’s attitude expressed in the menu:

We are unable always to accommodate vegetarians, as most French cooking involves eggs, creams and proteins.

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

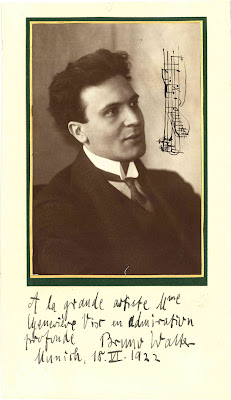

Bruno Walter In Minneapolis

Many music-lovers are unaware that Bruno Walter was the primary conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony for the orchestra’s 1922-1923 season. Walter’s title the season he led the Minneapolis Symphony was Chief Guest Conductor.

Emil Oberhoffer served as the orchestra’s Principal Conductor from 1903, the year the Minneapolis Symphony was founded, until 1922. In the latter year, Oberhoffer and the orchestra’s management had a fall-out, and Oberhoffer either resigned or was shoved aside.

Lacking a conductor for the following season, the Minneapolis Symphony approached Bruno Walter, who had recently resigned his position as Music Director of the old Court Opera in Munich. Germany was in political and economic crisis at the time—the period of post-war hyperinflation was at its peak—and Walter, like many German conductors in the early 1920s, was looking for work outside Germany. Walter agreed to come to the U.S. and tend the Minneapolis Symphony for a season.

It is unknown whether Walter or the orchestra contemplated a more permanent association at the time Walter was engaged. However, during the 1922-1923 season, the appearance of another guest conductor, Henri Verbrugghen, caused a sensation, and Verbrugghen was offered—and accepted—the post of Principal Conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony beginning with the 1923-1924 season. Verbrugghen remained the orchestra’s Principal Conductor until 1931, when he had to resign for reasons of health.

At the conclusion of the 1922-1923 season, Walter returned to Europe, where he was to hold several important posts for the next fifteen years. Walter fled Europe on November 1, 1939, exactly two months after the war started, and made the United States his home for the rest of his life.

After that 1922-1923 season, Walter was not again to appear with the Minneapolis Symphony until the Dimitri Mitropoulos era (1937-1949), when Walter returned to Minneapolis as a welcome guest conductor.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Piles Of Shtick From The Vaudeville Trunk

On Friday, Joshua and I went over to my older brother’s house. Our furniture from Boston was due to be delivered to my older brother’s house that day.

Both of my brothers took vacation days on Friday in order to assist in the day’s activities.

My sister-in-law contemplated taking my nephew and niece over to my parents’ house for the day in order to keep them out of everyone’s hair, but she decided to allow them to stay home and witness the installation of new things in their house.

Our Boston living room furniture was destined for my older brother’s den, which has been bereft of furniture since my older brother and his family moved into the house in early 2009.

The den now has bookshelves; a computer module—with two chairs—that accommodates two computer stations, a television and a sound station; a couch; two end tables; and four beautiful lamps that lend color to the room. We arranged everything to my brother’s specifications, and he now loves his den (and, for the first time, he will be able to use it). He now intends to work from home a couple of days a month—and my sister-in-law now intends to select window dressings and rugs for the room.

Our Boston bedroom furniture was destined for my nephew’s room. Since he left the crib, my nephew has slept on an antique daybed of spool design—but henceforth he will sleep on a large double bed (on which he now likes to jump up and down). Our only other item of bedroom furniture from Boston was a chest of drawers. It, too, now resides in my nephew’s bedroom.

Our Boston kitchen furniture consisted only of a table and four chairs. For now, the table and chairs are in my older brother’s basement, as are a few boxes of books and kitchenware and other odds and ends we had shipped home. These items will remain in my brother’s basement until Josh and I establish a permanent residence (our search for a permanent abode will get underway once Josh has taken the Minnesota Bar Exam and once we return from Britain).

On Friday night, Josh and I took my middle brother downtown for a night out.

We ate dinner at a popular restaurant that features new American cuisine. The menu was somewhat pretentious—and not greatly appealing—but we were able to assemble a decent meal. We ordered asparagus soup with king crab and lime; apricot-glazed stuffed quail; and raspberry shortcake. I suspect we shall never return to the restaurant—only two entrees on the menu seemed even remotely appealing, and the one we selected, the quail, was no more than minimally satisfactory.

After dinner, we attended Jungle Theater’s production of the Stephen Sondheim musical, “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum”. The presentation was the first musical staged by Jungle Theater in the company’s twenty-year history.

The production was not good. Everything was far too broadly played; the performers were having a better time than the audience.

“A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum”, from 1962, has enjoyed several commercially-successful revivals, but the appeal of the show escapes me.

The show is a farce, but the farce is not funny.

The show is a musical, but the music is not good.

Except for the famous opening number, the score for “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum” is supremely undistinguished. There are no hints of the genius Sondheim was to reveal eight years later in “Company”. (Sondheim has repeatedly remarked that the 1960s were fallow creative years for him. He has also stated that the constraints of the book of “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum” were, for him, stifling.)

“A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum” may be entirely dependent upon the skills of a fine director to bring the show to life. At Jungle Theater, the director merely unloosed piles of shtick from the vaudeville trunk. The anything-for-a-laugh onstage antics were incessant. They quickly became cornball, then tiresome, and finally exhausting.

It was a depressing evening. I never want to see the show again.

Both of my brothers took vacation days on Friday in order to assist in the day’s activities.

My sister-in-law contemplated taking my nephew and niece over to my parents’ house for the day in order to keep them out of everyone’s hair, but she decided to allow them to stay home and witness the installation of new things in their house.

Our Boston living room furniture was destined for my older brother’s den, which has been bereft of furniture since my older brother and his family moved into the house in early 2009.

The den now has bookshelves; a computer module—with two chairs—that accommodates two computer stations, a television and a sound station; a couch; two end tables; and four beautiful lamps that lend color to the room. We arranged everything to my brother’s specifications, and he now loves his den (and, for the first time, he will be able to use it). He now intends to work from home a couple of days a month—and my sister-in-law now intends to select window dressings and rugs for the room.

Our Boston bedroom furniture was destined for my nephew’s room. Since he left the crib, my nephew has slept on an antique daybed of spool design—but henceforth he will sleep on a large double bed (on which he now likes to jump up and down). Our only other item of bedroom furniture from Boston was a chest of drawers. It, too, now resides in my nephew’s bedroom.

Our Boston kitchen furniture consisted only of a table and four chairs. For now, the table and chairs are in my older brother’s basement, as are a few boxes of books and kitchenware and other odds and ends we had shipped home. These items will remain in my brother’s basement until Josh and I establish a permanent residence (our search for a permanent abode will get underway once Josh has taken the Minnesota Bar Exam and once we return from Britain).

On Friday night, Josh and I took my middle brother downtown for a night out.

We ate dinner at a popular restaurant that features new American cuisine. The menu was somewhat pretentious—and not greatly appealing—but we were able to assemble a decent meal. We ordered asparagus soup with king crab and lime; apricot-glazed stuffed quail; and raspberry shortcake. I suspect we shall never return to the restaurant—only two entrees on the menu seemed even remotely appealing, and the one we selected, the quail, was no more than minimally satisfactory.

After dinner, we attended Jungle Theater’s production of the Stephen Sondheim musical, “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum”. The presentation was the first musical staged by Jungle Theater in the company’s twenty-year history.

The production was not good. Everything was far too broadly played; the performers were having a better time than the audience.

“A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum”, from 1962, has enjoyed several commercially-successful revivals, but the appeal of the show escapes me.

The show is a farce, but the farce is not funny.

The show is a musical, but the music is not good.

Except for the famous opening number, the score for “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum” is supremely undistinguished. There are no hints of the genius Sondheim was to reveal eight years later in “Company”. (Sondheim has repeatedly remarked that the 1960s were fallow creative years for him. He has also stated that the constraints of the book of “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum” were, for him, stifling.)

“A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum” may be entirely dependent upon the skills of a fine director to bring the show to life. At Jungle Theater, the director merely unloosed piles of shtick from the vaudeville trunk. The anything-for-a-laugh onstage antics were incessant. They quickly became cornball, then tiresome, and finally exhausting.

It was a depressing evening. I never want to see the show again.

Monday, June 20, 2011

Guest Of Honor

This remarkable photograph was taken on January 11, 1925, at Steinway And Sons in Manhattan.

The photograph records a great event: musical New York’s official welcome extended to Wilhelm Furtwangler on the occasion of his first appearances in the United States. The reception was held on Furtwangler’s eighth day in New York.

A glittering array of legendary figures was present for the occasion.

Igor Stravinsky, Nikolai Medtner and Josef Hofman are in the front row.

Fritz Kreisler and Sergei Rachmaninoff are in the second row.

Aexander Siloti occupies the upper-right corner of the photograph.

Today it would be impossible to assemble a comparable group of musicians, as none such as a Stravinsky, a Furtwangler, a Kreisler, a Hofman or a Rachmaninoff exist.

Monday, June 13, 2011

Guests Of Honor

A February 10, 1937, Winterhilfe benefit concert attended by Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, and Emmy and Hermann Goering.

The venue for the concert: Berlin’s Philharmonie. The musicians: the Berlin Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwangler. The program: Weber’s “Der Freischutz” Overture, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 and Brahms’s Symphony No. 4.

The 1937 Winterhilfe benefit concert was a special occasion in more ways than one—it marked Furtwangler’s return to the concert platform after an absence of almost eight months. Furtwangler had not appeared in public since July 1936.

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Gloom Does Not Equal Profundity

Last evening, Joshua and I took my parents to Saint Paul to hear the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra in its final subscription program of the season.

Josh and I had not heard the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra in concert since April 2008.

Hard as it is for me to believe, Josh and I had attended only two SPCO concerts when we lived in the Twin Cities from June 2006 until August 2008. Consequently, last night was only the third time Josh had heard the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra in person.

Last night’s program was attractive, which is why we had obtained tickets.

The concert began with a performance of Schubert’s Offertory In B Flat Major, D. 963, a solemn composition for tenor, chorus and orchestra written in the month before Schubert’s death.

The Offertory, like so much of Schubert’s choral output, is very seldom performed in the United States. Indeed, I had never previously seen the work programmed.

Of less than ten minutes’ duration, the Offertory seemed a slight work in the Saint Paul performance; both the music and the performance struck me as neutral and uncommitted. The composition reminded me of the Deutsche Messe, one of Schubert’s least interesting works written for worship service. The Deutsche Messe, Schubert’s simplest and least typical mass setting, does not find the composer at his most inspired—and the Saint Paul performance of the Offertory offered no hints of inspiration, either.

The work of the orchestra and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Chorale was perfectly fine, but also perfectly bland. The tenor soloist was a local singer.

The evening’s conductor, Thomas Zehetmair, appeared as both soloist and conductor in the second work on the program, Hartmann’s Concerto Funebre.

Zehetmair has maintained Hartmann’s Concerto Funebre in his repertory for more than twenty years; he surely knows the piece as well as anyone alive, as he has played the piece countless times all over the world since the late 1980s.

I do not think that Hartmann was a good composer. Hartmann had assimilated the music of Bartok, Schoenberg, Berg and the French modernists—and had studied with Webern, with whom he had argued—yet Hartmann produced music that, while definitely of a modernist bent, lacked character, personality, freshness and appeal.

Everything Hartmann wrote reminds me of Weill’s Symphony No. 1. In Weill’s first symphony, the young composer had borrowed techniques from virtually every modernist composer then working in Central Europe. Weill’s Symphony No.1 was in essence a “study” symphony, the work of a student on the brink of maturation. The symphony was designed to demonstrate the young composer’s grasp of complicated forms and familiarity with “advanced” writing idioms—but it was not a symphony worth hearing “on the merits”. Written before the composer had acquired his individual voice, Weill’s Symphony No. 1 is a curiosity, a prelude to the much more successful Symphony No. 2.

In Hartmann’s lengthy composing career, Hartmann never proceeded beyond the stage Weill had inhabited while writing his youthful first symphony. There is an “everything but the kitchen sink” quality to Hartmann’s music; he borrowed techniques from everyone—but in the process he failed to find himself.

Hartmann, unlike Weill, never acquired an individual voice. The lack of an individual voice is the ultimate fatality for a composer—and provides the reason Hartmann’s music has never caught on, and probably never will catch on.

The Concerto Funebre, beautifully constructed on the printed page, is Hartmann’s most-frequently-performed composition. It is a serious, thoughtful, learned, even noble work—and yet the piece is a complete dud.

Although scored only for strings, the scoring is thick if not impenetrable (which is also true of Hartmann’s symphonies—Hartmann had studied the orchestration of Roussel rather than Ravel). The writing for solo violin is not grateful and does not “sound”—the violin does not soar above the orchestra as it must—and it is easy to understand why so few prominent violinists have placed the work into their active repertories.

Of greatest importance, the quality of ideas in Concerto Funebre is not high. Hartmann’s themes are mundane, his development of the themes even more mundane.

Concerto Funebre provides audiences with twenty minutes of earnest, well-meaning—and deadly—music. Its current performances, quite frequent, are more a tribute to the politics of the composer—he was in “internal exile” during the period of National Socialism—than to the quality of the composer's music.

Hartmann’s music may never have found its ideal interpreter.

Most conductors ignored Hartmann’s music during the composer’s lifetime.

Only a few conductors have learned and performed the symphonies since the composer’s death.

To date, the efforts of a handful of conductors on behalf of Hartmann have not revealed a body of work in need of discovery.

Rafael Kubelik certainly was unable to make anything of Hartmann’s symphonies—assuming Kubelik’s live recordings accurately represent his Hartmann interpretations, Kubelik brought no insight whatsoever to Hartmann. Ingo Metzmacher’s attempts to bring the Hartmann symphonies to life via modern studio recordings were not successful, either. Leon Botstein’s recorded interpretations of Hartmann’s symphonies were clumsy embarrassments.

If no conductor has been able to unlock Hartmann’s voice in the forty-eight years since the composer’s death, there probably is no voice to unlock.

One problem with Hartmann scores is that most were revised in the last decade of Hartmann’s life—with the result that the scores all sound startlingly alike. Hartmann compositions from the early 1930s sound exactly like Hartmann compositions from the early 1950s. The composer may have made an error in revising most of his scores late in life.

Another problem with Hartmann’s music is that Hartmann lacked a wide range of expression. Hartmann’s music expresses gloom, and little else—and, to my ears, the gloom is more earnest than deeply-felt. Gloom does not necessarily equal profundity, and I hear no profundity in Hartmann’s gloom.

Yet another problem with Hartmann’s music is the composer’s over-reliance upon the device of fugue. Whenever Hartmann needed to generate tension, or extend a movement, or bring things to a conclusion, he invariably inserted his personal version of a fugue into the proceedings. Unlike the fugues of Bach, the fugues of Hartmann are mechanical, and lack expression; they are mere academic tools—and they sound like academic tools.

Zehetmair’s performance of the Concerto Funebre last night sounded exactly like his 1990 Teldec recording of the work: a skillful, considered rendering of music—in various shades of gray—that fundamentally does not engage the ear or the mind.

Hartmann wrote his Concerto Funebre in 1939; the work was his personal reaction to Germany’s invasion and annexation of Czechoslovakia. Hartmann revised the work in 1959, when he gave the work its current title.

During the war, Hartmann had the luxury of remaining unemployed, a very unusual circumstance for a healthy male in wartime Germany. Hartmann lived in isolation and comfort outside Munich—his wife’s father was a wealthy manufacturer of ball bearings, and profited enormously from the war—and Hartmann enjoyed privileges unavailable to all but a handful of Germans.

Did earlier generations of German musicians hold such privilege against Hartmann? And boycott his music as a result?

I suspect not. Conductors that remained in Germany during the period of National Socialism generally avoided Hartmann’s music after the war, and conductors that emigrated from Germany on account of National Socialism also generally avoided Hartmann’s music after the war. Such would suggest that most conductors simply did not like the music Hartmann wrote.

I would like to know Twin Cities resident Stanislaw Skrowaczewski’s unvarnished thoughts about the music of Hartmann. Skrowaczewski recently completed a series of concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic in which either Skrowaczewski or the administration of the Berlin Philharmonic had programmed Hartmann’s final composition, Gesangsszene, a work for baritone and orchestra. Did Skrowaczewski himself initiate programming of the Hartmann composition, or was the conductor merely doing the Berlin Philharmonic a favor? Or was the programming of Gesangsszene all about baritone Matthias Goerne, and only about Matthias Goerne?

After intermission, the orchestra and chorus offered the work that had attracted us to the concert hall: Haydn’s Mass No. 14 (“Harmoniemesse”), the composer’s final mass setting. The mass derives its name from its prominent writing for winds.

Last night’s Haydn performance mirrored the Schubert performance: orchestral execution and choral execution were at a high level, yet the music-making was incomparably bland. The soloists, all local singers, made no impression. It was a disappointing account of a great score.

Based upon last night’s concert, I am diffident about Zehetmair’s skill as a conductor.

It was obvious that Zehetmair had not inspired the Saint Paul musicians, who gave Zehetmair workmanlike performances. Zehetmair revealed no ideas and demonstrated no personality in the Schubert or Haydn. From a pure performance perspective, Zehetmair was at his best in the Hartmann—the Minnesota musicians actually seemed modestly engaged by the piece—yet Zehetmair revealed nothing that would make me want to hear him often on the podium.

________________________________________________

On Friday night, my older brother and my sister-in-law went downtown to hear the Minnesota Orchestra play Copland’s “Appalachian Spring” (in the 1945 suite for full orchestra derived from the 1944 complete ballet score for chamber forces) and Orff’s “Carmina Burana”. They enjoyed the concert very much.

My nephew and niece were in our care while their parents were at the concert. Their mother brought them over in the middle of Friday afternoon, and they stayed with us overnight.

My middle brother joined us for the evening (and he, too, stayed overnight).

We had a great time, playing with the kids and their toys on the kitchen floor until dinnertime.

Josh and I prepared dinner so that my mother could mind my niece. We made a garden salad with numerous fresh vegetables. We made oven-fried chicken, the only fried chicken I can do successfully. We made a potato salad that included radishes, scallions and celery. We made baked beans. We made biscuits, some of which we ate with butter and some of which we ate with honey. For dessert, we made cherry crisp.

After dinner, we played table games until it was time for my nephew and niece to turn in.

On Saturday morning, we made buttermilk pancakes for breakfast. The kids like buttermilk pancakes served with brown sausages.

Not long after breakfast, their parents came to retrieve them and take them home—my brother’s family had things to do at home on Saturday—and the rest of us spent the day working on our Britain itinerary, which is nearing completion.

Today, after church, everyone came to my parents’ house.

We had grilled ham-and-cheese sandwiches for lunch.

This afternoon, while my niece and nephew took their naps, my parents went to the care facility to sit with my grandmother.

Tonight we had roast chicken with stuffing, mashed potatoes, homemade butter noodles, fresh green beans, corn-on-the-cob, fried red tomatoes and my mother’s version of Waldorf Salad. For dessert, we had angel food cake.

This week, my nephew will attend Bible School on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday.

On Friday, the movers are scheduled to deliver to my older brother’s house Josh’s and my furniture from Boston.

My project for the week, while Josh is immersed in his bar review materials: my mother’s kitchen, which I am going to clean from top to bottom. I am going to take apart all appliances and all fixtures and clean everything mercilessly; clean and oil the cabinets and all other wood items in the kitchen, including furniture and woodwork and wooden window blinds; and strip and wax the floor.

I may create such disruption that we shall not be able to eat all week.

Josh and I had not heard the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra in concert since April 2008.

Hard as it is for me to believe, Josh and I had attended only two SPCO concerts when we lived in the Twin Cities from June 2006 until August 2008. Consequently, last night was only the third time Josh had heard the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra in person.

Last night’s program was attractive, which is why we had obtained tickets.

The concert began with a performance of Schubert’s Offertory In B Flat Major, D. 963, a solemn composition for tenor, chorus and orchestra written in the month before Schubert’s death.

The Offertory, like so much of Schubert’s choral output, is very seldom performed in the United States. Indeed, I had never previously seen the work programmed.

Of less than ten minutes’ duration, the Offertory seemed a slight work in the Saint Paul performance; both the music and the performance struck me as neutral and uncommitted. The composition reminded me of the Deutsche Messe, one of Schubert’s least interesting works written for worship service. The Deutsche Messe, Schubert’s simplest and least typical mass setting, does not find the composer at his most inspired—and the Saint Paul performance of the Offertory offered no hints of inspiration, either.

The work of the orchestra and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Chorale was perfectly fine, but also perfectly bland. The tenor soloist was a local singer.

The evening’s conductor, Thomas Zehetmair, appeared as both soloist and conductor in the second work on the program, Hartmann’s Concerto Funebre.

Zehetmair has maintained Hartmann’s Concerto Funebre in his repertory for more than twenty years; he surely knows the piece as well as anyone alive, as he has played the piece countless times all over the world since the late 1980s.

I do not think that Hartmann was a good composer. Hartmann had assimilated the music of Bartok, Schoenberg, Berg and the French modernists—and had studied with Webern, with whom he had argued—yet Hartmann produced music that, while definitely of a modernist bent, lacked character, personality, freshness and appeal.

Everything Hartmann wrote reminds me of Weill’s Symphony No. 1. In Weill’s first symphony, the young composer had borrowed techniques from virtually every modernist composer then working in Central Europe. Weill’s Symphony No.1 was in essence a “study” symphony, the work of a student on the brink of maturation. The symphony was designed to demonstrate the young composer’s grasp of complicated forms and familiarity with “advanced” writing idioms—but it was not a symphony worth hearing “on the merits”. Written before the composer had acquired his individual voice, Weill’s Symphony No. 1 is a curiosity, a prelude to the much more successful Symphony No. 2.

In Hartmann’s lengthy composing career, Hartmann never proceeded beyond the stage Weill had inhabited while writing his youthful first symphony. There is an “everything but the kitchen sink” quality to Hartmann’s music; he borrowed techniques from everyone—but in the process he failed to find himself.

Hartmann, unlike Weill, never acquired an individual voice. The lack of an individual voice is the ultimate fatality for a composer—and provides the reason Hartmann’s music has never caught on, and probably never will catch on.

The Concerto Funebre, beautifully constructed on the printed page, is Hartmann’s most-frequently-performed composition. It is a serious, thoughtful, learned, even noble work—and yet the piece is a complete dud.

Although scored only for strings, the scoring is thick if not impenetrable (which is also true of Hartmann’s symphonies—Hartmann had studied the orchestration of Roussel rather than Ravel). The writing for solo violin is not grateful and does not “sound”—the violin does not soar above the orchestra as it must—and it is easy to understand why so few prominent violinists have placed the work into their active repertories.

Of greatest importance, the quality of ideas in Concerto Funebre is not high. Hartmann’s themes are mundane, his development of the themes even more mundane.

Concerto Funebre provides audiences with twenty minutes of earnest, well-meaning—and deadly—music. Its current performances, quite frequent, are more a tribute to the politics of the composer—he was in “internal exile” during the period of National Socialism—than to the quality of the composer's music.

Hartmann’s music may never have found its ideal interpreter.

Most conductors ignored Hartmann’s music during the composer’s lifetime.

Only a few conductors have learned and performed the symphonies since the composer’s death.

To date, the efforts of a handful of conductors on behalf of Hartmann have not revealed a body of work in need of discovery.

Rafael Kubelik certainly was unable to make anything of Hartmann’s symphonies—assuming Kubelik’s live recordings accurately represent his Hartmann interpretations, Kubelik brought no insight whatsoever to Hartmann. Ingo Metzmacher’s attempts to bring the Hartmann symphonies to life via modern studio recordings were not successful, either. Leon Botstein’s recorded interpretations of Hartmann’s symphonies were clumsy embarrassments.

If no conductor has been able to unlock Hartmann’s voice in the forty-eight years since the composer’s death, there probably is no voice to unlock.

One problem with Hartmann scores is that most were revised in the last decade of Hartmann’s life—with the result that the scores all sound startlingly alike. Hartmann compositions from the early 1930s sound exactly like Hartmann compositions from the early 1950s. The composer may have made an error in revising most of his scores late in life.

Another problem with Hartmann’s music is that Hartmann lacked a wide range of expression. Hartmann’s music expresses gloom, and little else—and, to my ears, the gloom is more earnest than deeply-felt. Gloom does not necessarily equal profundity, and I hear no profundity in Hartmann’s gloom.

Yet another problem with Hartmann’s music is the composer’s over-reliance upon the device of fugue. Whenever Hartmann needed to generate tension, or extend a movement, or bring things to a conclusion, he invariably inserted his personal version of a fugue into the proceedings. Unlike the fugues of Bach, the fugues of Hartmann are mechanical, and lack expression; they are mere academic tools—and they sound like academic tools.

Zehetmair’s performance of the Concerto Funebre last night sounded exactly like his 1990 Teldec recording of the work: a skillful, considered rendering of music—in various shades of gray—that fundamentally does not engage the ear or the mind.

Hartmann wrote his Concerto Funebre in 1939; the work was his personal reaction to Germany’s invasion and annexation of Czechoslovakia. Hartmann revised the work in 1959, when he gave the work its current title.

During the war, Hartmann had the luxury of remaining unemployed, a very unusual circumstance for a healthy male in wartime Germany. Hartmann lived in isolation and comfort outside Munich—his wife’s father was a wealthy manufacturer of ball bearings, and profited enormously from the war—and Hartmann enjoyed privileges unavailable to all but a handful of Germans.

Did earlier generations of German musicians hold such privilege against Hartmann? And boycott his music as a result?

I suspect not. Conductors that remained in Germany during the period of National Socialism generally avoided Hartmann’s music after the war, and conductors that emigrated from Germany on account of National Socialism also generally avoided Hartmann’s music after the war. Such would suggest that most conductors simply did not like the music Hartmann wrote.

I would like to know Twin Cities resident Stanislaw Skrowaczewski’s unvarnished thoughts about the music of Hartmann. Skrowaczewski recently completed a series of concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic in which either Skrowaczewski or the administration of the Berlin Philharmonic had programmed Hartmann’s final composition, Gesangsszene, a work for baritone and orchestra. Did Skrowaczewski himself initiate programming of the Hartmann composition, or was the conductor merely doing the Berlin Philharmonic a favor? Or was the programming of Gesangsszene all about baritone Matthias Goerne, and only about Matthias Goerne?

After intermission, the orchestra and chorus offered the work that had attracted us to the concert hall: Haydn’s Mass No. 14 (“Harmoniemesse”), the composer’s final mass setting. The mass derives its name from its prominent writing for winds.

Last night’s Haydn performance mirrored the Schubert performance: orchestral execution and choral execution were at a high level, yet the music-making was incomparably bland. The soloists, all local singers, made no impression. It was a disappointing account of a great score.

Based upon last night’s concert, I am diffident about Zehetmair’s skill as a conductor.

It was obvious that Zehetmair had not inspired the Saint Paul musicians, who gave Zehetmair workmanlike performances. Zehetmair revealed no ideas and demonstrated no personality in the Schubert or Haydn. From a pure performance perspective, Zehetmair was at his best in the Hartmann—the Minnesota musicians actually seemed modestly engaged by the piece—yet Zehetmair revealed nothing that would make me want to hear him often on the podium.

________________________________________________

On Friday night, my older brother and my sister-in-law went downtown to hear the Minnesota Orchestra play Copland’s “Appalachian Spring” (in the 1945 suite for full orchestra derived from the 1944 complete ballet score for chamber forces) and Orff’s “Carmina Burana”. They enjoyed the concert very much.

My nephew and niece were in our care while their parents were at the concert. Their mother brought them over in the middle of Friday afternoon, and they stayed with us overnight.

My middle brother joined us for the evening (and he, too, stayed overnight).

We had a great time, playing with the kids and their toys on the kitchen floor until dinnertime.

Josh and I prepared dinner so that my mother could mind my niece. We made a garden salad with numerous fresh vegetables. We made oven-fried chicken, the only fried chicken I can do successfully. We made a potato salad that included radishes, scallions and celery. We made baked beans. We made biscuits, some of which we ate with butter and some of which we ate with honey. For dessert, we made cherry crisp.

After dinner, we played table games until it was time for my nephew and niece to turn in.

On Saturday morning, we made buttermilk pancakes for breakfast. The kids like buttermilk pancakes served with brown sausages.

Not long after breakfast, their parents came to retrieve them and take them home—my brother’s family had things to do at home on Saturday—and the rest of us spent the day working on our Britain itinerary, which is nearing completion.

Today, after church, everyone came to my parents’ house.

We had grilled ham-and-cheese sandwiches for lunch.

This afternoon, while my niece and nephew took their naps, my parents went to the care facility to sit with my grandmother.

Tonight we had roast chicken with stuffing, mashed potatoes, homemade butter noodles, fresh green beans, corn-on-the-cob, fried red tomatoes and my mother’s version of Waldorf Salad. For dessert, we had angel food cake.

This week, my nephew will attend Bible School on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday.

On Friday, the movers are scheduled to deliver to my older brother’s house Josh’s and my furniture from Boston.

My project for the week, while Josh is immersed in his bar review materials: my mother’s kitchen, which I am going to clean from top to bottom. I am going to take apart all appliances and all fixtures and clean everything mercilessly; clean and oil the cabinets and all other wood items in the kitchen, including furniture and woodwork and wooden window blinds; and strip and wax the floor.

I may create such disruption that we shall not be able to eat all week.

Saturday, June 11, 2011

Music Notes From The Past

The Minneapolis Symphony was founded in 1903. Its principal conductor, from 1903 until 1922, was Emil Oberhoffer (1867-1933), a German-born conductor who emigrated to the United States in 1885 and who became an American citizen in 1893.

In addition to serving as founding conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony, Oberhoffer—composer, conductor, organist, pianist, violinist, choral trainer, lecturer—was the first head of the Music Department of the University Of Minnesota.

The press sheet below, from 1916, offers extended excerpts from reviews the Minneapolis Symphony received during its 1916 tour of the East Coast.

The reviews are glowing—and appear to be written by knowledgeable persons, no less.

If the reviews are reliable, by 1916 the Minneapolis Symphony was deemed equal, if not superior, to the Boston Symphony of Karl Muck and the Chicago Symphony of Frederick Stock—and vastly superior to the New York Symphony of Walter Damrosch, the New York Philharmonic of Josef Stransky and the Philadelphia Orchestra of Leopold Stokowski.

Indeed, the Minneapolis Symphony, from approximately 1910 until approximately 1950, was generally considered to be one of America’s top five orchestras, a few steps above Cincinnati, Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Saint Louis—and on par with the orchestras of Boston, Chicago, New York and Philadelphia. (No other American orchestras during this period were considered to be of any importance whatsoever; this is so even though they may have enjoyed the services of prominent conductors, such as Los Angeles, for a time guided by Otto Klemperer, and San Francisco, for a time guided by Pierre Monteux.) It was the rise of the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell that knocked the Minneapolis Symphony from the pedestal.

________________________________________________

Many music-lovers are unaware that the Twin Cities supported two major orchestras early in the 20th Century.

The Saint Paul Symphony was a major ensemble from 1905 until 1914. In the latter year, the orchestra disbanded because there were insufficient guarantors for the 1914-1915 season and because too many of the orchestra’s musicians were trapped in Germany with the onset of World War I.

In the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, American orchestras were staffed with numerous German players who would routinely return to Germany for the summer months. In August 1914, these players found it impossible to leave Europe and return to America, as quarantines were widely imposed throughout Central Europe and as ocean-crossings from the continent—but not from Britain—were largely halted. (In addition, many players found themselves drafted into the armies of The Central Powers). The loss of German players was significantly to impact musical activity all over the United States for years to come.

The conductor of the Saint Paul Symphony for the duration of its existence was Walter Henry Rothwell (1872-1927). Rothwell had been a student of Anton Bruckner and assistant to Gustav Mahler while Mahler had served as conductor of the Hamburg Opera. Five years after the Saint Paul Symphony folded, Rothwell became founding conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

During its short existence, the Saint Paul Symphony was generally deemed superior to the Minneapolis Symphony, with better conductors, better guest artists, and more serious programs.

Unlike the Minneapolis Symphony, the Saint Paul Symphony never toured—the Minneapolis Symphony began aggressive, weeks-long tours of the East Coast no later than 1912, and continued such tours well into the 1950s—and, as a result, the Saint Paul Symphony was never as widely-known to the rest of the country as its Twin Cities competitor (although it was known and respected within the orchestra field—its best musicians were routinely poached by other leading ensembles).

The Saint Paul Symphony is mostly forgotten today. Even music-lovers in the Twin Cities are largely unaware of its former existence.

In addition to serving as founding conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony, Oberhoffer—composer, conductor, organist, pianist, violinist, choral trainer, lecturer—was the first head of the Music Department of the University Of Minnesota.

The press sheet below, from 1916, offers extended excerpts from reviews the Minneapolis Symphony received during its 1916 tour of the East Coast.

The reviews are glowing—and appear to be written by knowledgeable persons, no less.

If the reviews are reliable, by 1916 the Minneapolis Symphony was deemed equal, if not superior, to the Boston Symphony of Karl Muck and the Chicago Symphony of Frederick Stock—and vastly superior to the New York Symphony of Walter Damrosch, the New York Philharmonic of Josef Stransky and the Philadelphia Orchestra of Leopold Stokowski.

Indeed, the Minneapolis Symphony, from approximately 1910 until approximately 1950, was generally considered to be one of America’s top five orchestras, a few steps above Cincinnati, Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Saint Louis—and on par with the orchestras of Boston, Chicago, New York and Philadelphia. (No other American orchestras during this period were considered to be of any importance whatsoever; this is so even though they may have enjoyed the services of prominent conductors, such as Los Angeles, for a time guided by Otto Klemperer, and San Francisco, for a time guided by Pierre Monteux.) It was the rise of the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell that knocked the Minneapolis Symphony from the pedestal.

________________________________________________

Many music-lovers are unaware that the Twin Cities supported two major orchestras early in the 20th Century.

The Saint Paul Symphony was a major ensemble from 1905 until 1914. In the latter year, the orchestra disbanded because there were insufficient guarantors for the 1914-1915 season and because too many of the orchestra’s musicians were trapped in Germany with the onset of World War I.

In the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, American orchestras were staffed with numerous German players who would routinely return to Germany for the summer months. In August 1914, these players found it impossible to leave Europe and return to America, as quarantines were widely imposed throughout Central Europe and as ocean-crossings from the continent—but not from Britain—were largely halted. (In addition, many players found themselves drafted into the armies of The Central Powers). The loss of German players was significantly to impact musical activity all over the United States for years to come.

The conductor of the Saint Paul Symphony for the duration of its existence was Walter Henry Rothwell (1872-1927). Rothwell had been a student of Anton Bruckner and assistant to Gustav Mahler while Mahler had served as conductor of the Hamburg Opera. Five years after the Saint Paul Symphony folded, Rothwell became founding conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

During its short existence, the Saint Paul Symphony was generally deemed superior to the Minneapolis Symphony, with better conductors, better guest artists, and more serious programs.

Unlike the Minneapolis Symphony, the Saint Paul Symphony never toured—the Minneapolis Symphony began aggressive, weeks-long tours of the East Coast no later than 1912, and continued such tours well into the 1950s—and, as a result, the Saint Paul Symphony was never as widely-known to the rest of the country as its Twin Cities competitor (although it was known and respected within the orchestra field—its best musicians were routinely poached by other leading ensembles).

The Saint Paul Symphony is mostly forgotten today. Even music-lovers in the Twin Cities are largely unaware of its former existence.

Thursday, June 09, 2011

Haydn, Again

For Joshua and me, our concert season began last autumn with a significant dose of Haydn—four symphonies, two performed by The Handel And Haydn Society and two performed by the Boston Symphony—and it will end on Saturday night with a performance of Haydn’s final mass, Mass No. 14 (“Harmoniemesse”), to be performed by the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra.

Both Twin Cities orchestras will end their subscription seasons this coming weekend, and both ensembles will feature important choral works in their final programs.

In addition to the SPCO concluding its season with the Haydn Harmoniemesse, the Minnesota Orchestra will close its season with Orff’s “Carmina Burana”.

Josh and I shall skip the Orff. Unlike many music lovers, I do not despise and I do not disparage the Orff—I think it is a magnificent piece of music—but I am not in the mood to hear “Carmina Burana” and Josh is not in the mood to hear “Carmina Burana”.

My parents are not in the mood to hear “Carmina Burana”, either—and they have given their subscription tickets to my older brother and my sister-in-law, who shall go to the concert tomorrow night in my parents’ stead. It is not often that my older brother and my sister-in-law attend orchestral concerts, but I believe they will enjoy “Carmina Burana”. As for us, my parents and Josh and I shall have the pleasure of keeping my nephew and niece while their parents have a rare night out.

My parents, who very seldom attend SPCO concerts, want to hear the Harmoniemesse. They will join Josh and me for the Saturday night concert in Saint Paul.

We will probably not attend any Minnesota Orchestra summer concerts. Only one event, the concert presentation of Richard Strauss’s “Der Rosencavalier”, holds some slight interest for us, but I believe we shall forego “Rosencavalier”. Minnesota Orchestra summer concerts are not fully rehearsed, the “Rosencavalier” conductor, Andrew Litton, is not noted for his Strauss interpretations, the singers engaged are unknown in the U.S. and enjoy only minor careers in Europe—and, above all, we are informed that the score to the opera will be cut. All of these factors make a concert presentation of Strauss’s opera unappealing.

For us, this may be a summer of musicals. Four local theater companies will mount musicals this summer, and we may attempt to catch them all: “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum”, “Guys And Dolls”, “The Fantasticks” and “Oklahoma!”.

Three of the musicals will not be miked, and real instruments—and not synthesizers—will be used for orchestral support. As for the fourth musical, “Guys And Dolls”, we do not yet know the sound production policy for the show and we do not yet know the orchestral forces to be engaged.

Two reasons the American musical has died: cast members are outfitted with body microphones; and synthesizers are used instead of orchestras. In the Twin Cities, except for touring productions straight from Broadway, microphones and synthesizers are generally not utilized for musicals. This makes attending musicals in Minneapolis much more rewarding than attending musicals in New York.

Even the Guthrie Theater will offer a musical presentation this summer: a Gilbert And Sullivan operetta, “H.M.S Pinafore”. We may or we may not go.

Both Twin Cities orchestras will end their subscription seasons this coming weekend, and both ensembles will feature important choral works in their final programs.

In addition to the SPCO concluding its season with the Haydn Harmoniemesse, the Minnesota Orchestra will close its season with Orff’s “Carmina Burana”.

Josh and I shall skip the Orff. Unlike many music lovers, I do not despise and I do not disparage the Orff—I think it is a magnificent piece of music—but I am not in the mood to hear “Carmina Burana” and Josh is not in the mood to hear “Carmina Burana”.

My parents are not in the mood to hear “Carmina Burana”, either—and they have given their subscription tickets to my older brother and my sister-in-law, who shall go to the concert tomorrow night in my parents’ stead. It is not often that my older brother and my sister-in-law attend orchestral concerts, but I believe they will enjoy “Carmina Burana”. As for us, my parents and Josh and I shall have the pleasure of keeping my nephew and niece while their parents have a rare night out.

My parents, who very seldom attend SPCO concerts, want to hear the Harmoniemesse. They will join Josh and me for the Saturday night concert in Saint Paul.

We will probably not attend any Minnesota Orchestra summer concerts. Only one event, the concert presentation of Richard Strauss’s “Der Rosencavalier”, holds some slight interest for us, but I believe we shall forego “Rosencavalier”. Minnesota Orchestra summer concerts are not fully rehearsed, the “Rosencavalier” conductor, Andrew Litton, is not noted for his Strauss interpretations, the singers engaged are unknown in the U.S. and enjoy only minor careers in Europe—and, above all, we are informed that the score to the opera will be cut. All of these factors make a concert presentation of Strauss’s opera unappealing.

For us, this may be a summer of musicals. Four local theater companies will mount musicals this summer, and we may attempt to catch them all: “A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum”, “Guys And Dolls”, “The Fantasticks” and “Oklahoma!”.

Three of the musicals will not be miked, and real instruments—and not synthesizers—will be used for orchestral support. As for the fourth musical, “Guys And Dolls”, we do not yet know the sound production policy for the show and we do not yet know the orchestral forces to be engaged.

Two reasons the American musical has died: cast members are outfitted with body microphones; and synthesizers are used instead of orchestras. In the Twin Cities, except for touring productions straight from Broadway, microphones and synthesizers are generally not utilized for musicals. This makes attending musicals in Minneapolis much more rewarding than attending musicals in New York.

Even the Guthrie Theater will offer a musical presentation this summer: a Gilbert And Sullivan operetta, “H.M.S Pinafore”. We may or we may not go.

In Fernem Land

Wednesday, June 08, 2011

Repeating And Reformulating

Last night Joshua and I and my parents went downtown to hear the Minnesota Orchestra play music by Beethoven and Sibelius. Despite the fact that yesterday was a Tuesday, last night’s concert was part of the regular subscription series.

My parents have always had the Friday night subscription, but they had exchanged last Friday’s tickets for tickets to last night’s concert because my mother had wanted to hold Josh’s graduation celebration Friday night, the first “real” night Josh and I were home.

It is interesting to compare the Minnesota Orchestra, which I had not heard since Thanksgiving 2008, with the Boston Symphony, the orchestra I have heard most often the last three years.

Both orchestras are fine orchestras, but neither orchestra arises to the exalted standard of the ensembles in Amsterdam, Berlin, Chicago, Cleveland, Dresden, Leipzig, Philadelphia and Vienna. I would categorize the Minnesota Orchestra and the Boston Symphony as upper-tier regional orchestras, the former orchestra on a short-term upward trajectory and the latter on a long-term downward spiral.

The Boston Symphony’s sound is superior to that of the Minnesota Orchestra. The sound of the Boston Symphony has more body and color and depth, as well as more light and shade, than the sound of the Minnesota Orchestra.

The Boston sound is also much richer, which is not necessarily a good thing—the richness of the Boston sound is largely artificial and inflated, imposed upon the musicians by James Levine. To my ears, the current Boston sound is not pleasing; it is an unsuccessful attempt on the part of Levine to replicate the sound of the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert Von Karajan. However, whereas Karajan drew thousands of shades and textures from his Berlin musicians, most often with astonishing transparency throughout the entire dynamic range, Levine obtains primarily volume and mass from the current Boston players. The result: an unpleasant and unsophisticated thickness and heaviness and inflexibility of sound, the very antithesis of Karajan’s objective in Berlin.

In its current state, the Boston Symphony sounds better under skilled guest conductors than when conducted by its recent Music Director. During the last three seasons, Boston sounded at its best under Christoph Dohnanyi and Bernard Haitink, both of whom toned down the Levine beefiness and both of whom obtained much greater transparency (and much better orchestral balance) than Levine ever was able to muster from the musicians.

The current Music Director of the Minnesota Orchestra, Osmo Vanska, favors a much leaner sound than the sound Levine attempted to create in Boston. Vanska treasures clarity above richness; he seeks a sound with a cutting edge, not the kind of luxuriant, upholstered deep sound Levine tried—without success—to create in Boston.

I have no objection to a lean sound, but the sound of today’s Minnesota Orchestra is characterized by a plainness that would be never be tolerated among world-class ensembles. There is a one-dimensional, generic sameness about the Minnesota Orchestra’s sound—in music of all periods—that quickly becomes tiresome.

On the other hand, the level of ensemble is now higher in Minneapolis than in Boston. Even though there is an unmistakable, heavily-drilled “bandmaster” quality to the playing of the Minneapolis musicians, the Minnesota Orchestra is much more unanimous in its attacks and releases than the Boston Symphony. The playing in Minnesota is more accurate, more alert and livelier than what I had become accustomed to in Boston.

The brass section is the finest section of the current Minnesota Orchestra. The Minnesota brass section puts the brass section of the Boston Symphony to shame (although I grant that the brass section has long been the weak link in Boston).

Neither orchestra has a distinguished array of winds. The winds in Chicago, Cleveland and Philadelphia are in an entirely different class than the winds in Minneapolis or Boston.

What ultimately tips the balance slightly in favor of Boston is that the Boston Symphony displays a higher level of collective music-making than the Minnesota Orchestra. Remnants of the old Boston magic may still be heard on occasion; I heard isolated moments in Boston performances under Dohnanyi, Haitink, Colin Davis and Charles Dutoit in which the musicians suddenly took off like a flight of birds, as if the ghost of Charles Munch had appeared in Symphony Hall.

In Minnesota, the musicians do Vanska’s bidding, and they do it very well—but Vanska appears to generate the entire performance himself, with little real input from the souls of the players. In great orchestras, players give as much as they receive—and the musicians of the Minnesota Orchestra are still very much in the receiving stage. A better roster of guest conductors might contribute toward righting the equation.

The Beethoven work on last night’s program was the Piano Concerto No. 3. I last heard the Minnesota Orchestra play Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 three years ago, when Alfred Brendel performed the work in his final Twin Cities appearance (Vanska had been on the podium that night, too).

The Third is my favorite Beethoven piano concerto. I readily acknowledge that the Fourth and Fifth concertos are more original, feature more sublime slow movements and attempt a wider array of emotion than the Third—yet the Third is closest to my heart. In the Third, Beethoven was in the process of expanding the scale and scope of the concerto as an art form, yet the composition retains the pure Classicism of Mozart. In his Piano Concerto No. 3, Beethoven obtained perfection.

The pianist last evening was Yevgeny Sudbin, a Russian pianist who has appeared often in Minneapolis. Sudbin is in the process of recording the Beethoven concertos with Vanska and the Minnesota Orchestra.

I heard no special qualities in Sudbin’s playing. He was less overtly Romantic than many Russian pianists, current and past, but I found Sudbin otherwise unremarkable. On a few occasions, I thought Sudbin’s playing tended toward the precious and coy, which I find annoying if not grating in Beethoven.

Last night, Vanska was less mannered in the Beethoven than he had been three years ago, which was all to the good. He was less fierce in emphasizing dynamic contrasts, and more flexible in shaping the musical line. There was a more natural flow to last night’s performance than what had been presented in March 2008.

The Sibelius work on the program was the Symphony No. 2.

The Sibelius Symphony No. 2 is Vanska’s party piece. He generally programs the Sibelius Symphony No. 2 when making an appearance as guest conductor of an orchestra for the first time. Vanska performances of the Sibelius Second have been acclaimed all over the world.

I do not like Vanska’s Sibelius. In Sibelius, as in everything else, Vanska over-conducts. He is too intervening; he cannot leave well enough alone. Everything he conducts sounds forced, stressed, unduly emphasized. Hearing Vanska conduct is like watching a documentary propaganda film from the 1930s.

Audiences respond to Vanksa because of his intensity. The man has undeniable intensity.

An intense performance, however, is not the same thing as a good performance. On the whole, I find Vanska’s performances wearying—unyielding and unsubtle. I felt exhausted and beaten down at the conclusion of last night's Sibelius Second; the performance, simply put, was overstated.

Next week, the Minnesota Orchestra will record the Sibelius Symphony No. 2. It, along with the Symphony No. 5, will be the first release of an intended Sibelius cycle. The upcoming cycle will be Vanska’s second recorded Sibelius cycle—and will be made for the same label as his first.

Opening last night’s program was a composition by Aaron Kernis. Titled “Concerto With Echoes”, the piece was inspired by Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 and is scored for chamber ensemble (“Concerto With Echoes” was commissioned by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and premiered in 2009).

In three movements and of fifteen-minute duration, “Concerto With Echoes” is bland, faceless music, without personality and without profile (and without a single genuine—or original—idea). The score is, however, “accessible”—there is nothing in the least challenging about “Concerto With Echoes”—and skillfully orchestrated.

Kernis is a very unlucky man. In his youth, he never experienced the necessary epiphany, while listening to the music of Gyorgy Ligeti or Witold Lutoslawski or Elliott Carter, that caused him to ask himself: “Why am I thinking of becoming a composer? Whatever gave me such a bizarre notion? I could never write anything half so original. I could never write anything of such depth. I could never write anything approaching such a masterful display of craft. God simply did not grant me such genius. I need to get over the idea of becoming a composer, and focus on something else to do with my life. The best I could ever do as a composer would be to repeat and reformulate someone else’s third-rate, stale ideas.”

Alas, having never been so fortunate as to experience the necessary epiphany, Kernis entered the field of musical composition—and duly began repeating and reformulating the third-rate, stale ideas of others. Kernis rejected modernism, as it was fashionable to do in the U.S. at the time he was a composition student, and became an “eclectic” composer, borrowing bits and pieces from a wide array of other popular styles in order to assemble his profoundly undistinguished and unimaginative compositions.

More arranger than composer, Kernis more properly should have devoted his very limited set of skills to the art of scoring television films. Such is his natural realm.

My parents have always had the Friday night subscription, but they had exchanged last Friday’s tickets for tickets to last night’s concert because my mother had wanted to hold Josh’s graduation celebration Friday night, the first “real” night Josh and I were home.

It is interesting to compare the Minnesota Orchestra, which I had not heard since Thanksgiving 2008, with the Boston Symphony, the orchestra I have heard most often the last three years.

Both orchestras are fine orchestras, but neither orchestra arises to the exalted standard of the ensembles in Amsterdam, Berlin, Chicago, Cleveland, Dresden, Leipzig, Philadelphia and Vienna. I would categorize the Minnesota Orchestra and the Boston Symphony as upper-tier regional orchestras, the former orchestra on a short-term upward trajectory and the latter on a long-term downward spiral.

The Boston Symphony’s sound is superior to that of the Minnesota Orchestra. The sound of the Boston Symphony has more body and color and depth, as well as more light and shade, than the sound of the Minnesota Orchestra.

The Boston sound is also much richer, which is not necessarily a good thing—the richness of the Boston sound is largely artificial and inflated, imposed upon the musicians by James Levine. To my ears, the current Boston sound is not pleasing; it is an unsuccessful attempt on the part of Levine to replicate the sound of the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert Von Karajan. However, whereas Karajan drew thousands of shades and textures from his Berlin musicians, most often with astonishing transparency throughout the entire dynamic range, Levine obtains primarily volume and mass from the current Boston players. The result: an unpleasant and unsophisticated thickness and heaviness and inflexibility of sound, the very antithesis of Karajan’s objective in Berlin.

In its current state, the Boston Symphony sounds better under skilled guest conductors than when conducted by its recent Music Director. During the last three seasons, Boston sounded at its best under Christoph Dohnanyi and Bernard Haitink, both of whom toned down the Levine beefiness and both of whom obtained much greater transparency (and much better orchestral balance) than Levine ever was able to muster from the musicians.

The current Music Director of the Minnesota Orchestra, Osmo Vanska, favors a much leaner sound than the sound Levine attempted to create in Boston. Vanska treasures clarity above richness; he seeks a sound with a cutting edge, not the kind of luxuriant, upholstered deep sound Levine tried—without success—to create in Boston.

I have no objection to a lean sound, but the sound of today’s Minnesota Orchestra is characterized by a plainness that would be never be tolerated among world-class ensembles. There is a one-dimensional, generic sameness about the Minnesota Orchestra’s sound—in music of all periods—that quickly becomes tiresome.

On the other hand, the level of ensemble is now higher in Minneapolis than in Boston. Even though there is an unmistakable, heavily-drilled “bandmaster” quality to the playing of the Minneapolis musicians, the Minnesota Orchestra is much more unanimous in its attacks and releases than the Boston Symphony. The playing in Minnesota is more accurate, more alert and livelier than what I had become accustomed to in Boston.