The Saturday evening, January 22, program at New York City Ballet was devoted to three George Balanchine works: “Mozartiana”, “The Prodigal Son” and “Stars And Stripes”.

It was the only performance of the weekend in which Joshua had already seen all three ballets on the program (although not all had been danced by New York City Ballet). In

February 2008, Josh and I had seen New York City Ballet dance “Mozartiana”. In

May 2009, we had attended Boston Ballet’s presentation of “The Prodigal Son”. In

October 2010, we had witnessed “Stars And Stripes” at New York City Ballet.

“Mozartiana” is danced to Tchaikovsky’s Orchestral Suite No. 4 (“Mozartiana”). It was created for 1981’s Tchaikovsky Festival at New York City Ballet and was Balanchine’s last major work.

January 22 was my fourth encounter with “Mozartiana”—and I do not appreciate the ballet. As currently danced at NYCB, the ballet is slender and amorphous, lacking in profile.

“Mozartiana” was created for Suzanne Farrell—and the ballet may be intrinsically tied to Farrell’s special gifts.

Many knowledgeable ballet-goers have claimed that “Mozartiana” worked only with Farrell at its center. Other knowledgeable ballet-goers have argued that the ballet never worked, even with Farrell as its foundation.

I obviously was never able to see Farrell in “Mozartiana”—although my parents did—but “Mozartiana” has come and gone, without impression, the four times I have seen the ballet (with four different ballerinas dancing the Farrell role). The principal role may be too subtle for any ballerina other than its creator to carry—and the principal role is the heart and sole of the work.

I am not confident that Peter Martins is wise to retain “Mozartiana” in NYCB’s repertory. As long as there is no NYCB ballerina capable of breathing life into “Mozartiana”, the ballet may be better served by a prolonged absence. “Mozartiana” has never fully captured the interest of the NYCB audience whenever I was in the house, and I am told that audience reception has been cool since the work’s unveiling.

The January 22 performance of “The Prodigal Son” was very, very fine. It probably was the finest presentation of “The Prodigal Son” I have ever seen. The principals were excellent—the Siren perhaps a touch too icy and knowing, and not as threatening as she might have been—and the supporting cast members faultless, each bringing his or her full energy and attention to the respective role. The company clearly loves presenting this key masterpiece, despite decades of overexposure, and the NYCB staging remains in superb shape. “The Prodigal Son” is among the most indestructible of all Balanchine works.

“The Prodigal Son” was the first Balanchine ballet I experienced (excepting Balanchine’s “The Nutcracker”). I first saw “The Prodigal Son” when I was thirteen years old. The ballet made a great impression on me at the time, as it does on everyone, and “The Prodigal Son” remains one of my favorite Balanchine works. It is the only Expressionist ballet by Balanchine that remains in the repertory, and it is the only Balanchine ballet that European ballet companies have managed to dance convincingly (almost certainly because of its Expressionist roots). If Balanchine had died in 1929 after completing “The Prodigal Son” at age 25, his name would nonetheless be a permanent fixture in the annals of dance.

Prokofiev intensely disliked Balanchine’s choreography for “The Prodigal Son”. The composer apparently envisioned a more restrained and naturalistic choreographic treatment of his score—although the music certainly supports Balanchine’s approach—and refused to pay Balanchine royalties, keeping them to himself. Balanchine had the last laugh: his choreography is more memorable than Prokofiev’s score.

The title role is one of the greatest and most-sought male roles in the entire ballet repertory. Serge Lifar was the first Prodigal Son (imposed upon Balanchine by Sergei Diaghilev). Three decades later, the role was to make Edward Villella a star. Mikhail Baryshnikov became indelibly associated with the role once he defected to the West. The latter two portrayals are preserved on film, and are electrifying.

There is no male dancer on NYCB’s current roster that can give a “star” performance of the title role. Nonetheless, the ballet itself always registers.

The January 22 performance of “Stars And Stripes” was better than the performance we had attended in October. The January performance was crisper, and had a touch of flamboyance. I attribute the extra sparkle to the dancers offering their very best on the occasion of Balanchine’s birthday.

Three ballet performances in the course of little more than twenty-four hours did not fatigue Josh and me in the least. The New York City Ballet repertory is so rich, and the dancing of such a high standard, that we were more-or-less enthralled the whole time.

________________________________________________

Persons who were regular visitors to The New York State Theater during Balanchine’s lifetime are always quick to note that the Balanchine repertory at NYCB has deteriorated significantly since the master’s death. Directly or indirectly, the fault is invariably placed at the feet of Peter Martins.

Much of the deterioration, I suspect, was inevitable. Ballets cannot be frozen, preserved exactly as they were at some fixed point in time.

My parents tell me that the differences between performances during Balanchine’s lifetime and current performances at NYCB are most conspicuous in the way principal roles are now danced in Balanchine ballets. Principal dancing is not as specific and detailed as it was thirty and forty years ago. Balanchine’s personal coaching of principal dancers resulted in performances of greater individuality and expressiveness than may be seen today (and this is so despite Balanchine’s oft-cited dictum that he did not want his dancers to display “personality”).

On the other hand, according to my parents, today’s corps work at NYCB is at a much higher standard than it ever was during Balanchine’s lifetime. Further, the company no longer retains dead wood on its roster, which was not true when Balanchine himself was in charge. (Balanchine was steadfastly loyal to his dancers, even after they were no longer capable of giving effortless performances. My parents tell me that they witnessed innumerable performances at NYCB in the 1970s totally ruined by the presence of an aging, well-past-his-prime Jacques D’Amboise.)

Robert Gottlieb is today’s finest chronicler of the work of New York City Ballet. A former Board member of the company (thrown off the Board by an irate Martins, unhappy with Gottlieb’s publication of a celebrated Arlene Croce essay, an essay sharply critical of Martins), Gottlieb’s command of the Balanchine repertory is second to none among active dance writers.

Gottlieb must be read with a grain of salt because his tendency is to over-praise and under-praise. Eighty per cent of the time, Gottlieb is too harsh on the company. Twenty per cent of the time, Gottlieb lavishes undue praise. A passionate admirer of Balanchine, Gottlieb is too close to the company and its distinguished history to be completely objective in his assessments (although his writing remains essential reading).

Gottlieb has, for years, laid out the shortcomings of the Martins directorship, and Gottlieb has done so in great detail and with some eloquence. Gottlieb’s writing is the most valuable record of the company’s work over the last decade, and it is of historic importance (and must be read alongside Miss Croce’s work from the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s).

It has never bothered me that Gottlieb, Croce and others have criticized Martins, more or less relentlessly, since Martins assumed NYCB’s directorship. Martins’s own choreography is not valuable, his development of dancers has been disappointing, and the work of guest choreographers at NYCB has been extremely spotty (if not worse).

Martins has been prone to allow certain Balanchine works virtually to disappear from the repertory. There are key Balanchine masterpieces I have never seen—“Gounod Symphony” being a prominent example—because Martins has not revived the ballets.

Certain audience-pleasing works have been presented endlessly during the Martins regime. The dances from “West Side Story” surely have no place in NYCB’s repertory, yet they have become such a regular feature of NYCB programs that it has become difficult to avoid them.

Martins’s reliance upon full-length story ballets has been one of the most troubling themes of his directorship—and even if one assumes that NYCB should enter this particular arena, Martins’s own productions of the classics have been disastrous if “Swan Lake” and “Romeo And Juliet” may be used as guides—and accusations of a deliberate “dumbing down” of the repertory have some merit.

No doubt Martins’s oft-criticized tenure at NYCB is in its winding-down phase, if only because of Martins’s advancing age. In the next few years, someone else will be installed to become the standard-bearer and chief preserver of the Balanchine repertory.

The future of NYCB, however, may not be bright.

There is no obvious person waiting in the wings to replace Martins. Persons with the greatest command of Balanchine’s work, and possessing the most profound understanding of the Balanchine aesthetic, are the same age as Martins, or older still, and thus unlikely to be selected.

The succession, I predict, will not be a smooth one.

My instinct tells me that Martins’s successor will be someone unsuitable—someone such as Frenchman Benjamin Millepied, who has never developed a penetrating command of Balanchine style but who is very skilled at self-promotion—and that deterioration of the Balanchine repertory will continue, ultimately reaching a point at which Balanchine style as we know it today will virtually disappear.

The disappearance of the Balanchine style will be a tragedy of sorts—but the tragedy will be an inevitable one. Resistance is futile.

Ballet cycles are short. Ballet is an art form in which nothing is set. The passing of an influential figure in ballet will result in the passing of an influential style. In that sense, the ballet world resembles nothing so much as the temporal world of fashion.

Despite dance notation, texts in ballet are unlike texts in literature or music. In literature and music, texts are fixed. Ballet texts, in contrast, are living texts. Ballet texts are set on the human body and are handed down, generation by generation, via retired dancers coaching active dancers. Each revival of a ballet is one part preservation, one part renewal, one part recreation and one part re-composition—and, over time, re-composition is destined to assume the upper hand.

We are living in the tail end of The Balanchine Era—and its death will be part of a natural cycle.

Having missed the high period of Balanchine Classicism, I at least have been fortunate enough to have witnessed the remnants of a fast-disappearing epoch.

Better that, I think, than to have missed out entirely.

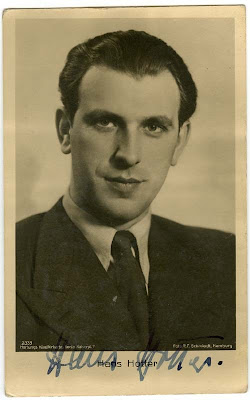

This striking photograph is the work of Erwin Blumenfeld (1897-1969), the German-born American photographer who fled to the U.S. in 1941 from Occupied France (where he had been placed in detention by German officials immediately after The Fall Of France).

This striking photograph is the work of Erwin Blumenfeld (1897-1969), the German-born American photographer who fled to the U.S. in 1941 from Occupied France (where he had been placed in detention by German officials immediately after The Fall Of France).